On the heels of first contact with an alien species in 2438, the rapid colonization of Virgil in the early twenty-fifth century sparked an expansion movement that lasted for centuries. The transformation of Virgil I from a desolate rocky world into a lush and thriving settlement seemed proof of Humanity’s newfound dominion over the stars, and many were eager to find more worlds to further solidify our standing. Formalized by the UNE government as Project Far Star, a concentrated effort to seed Human civilization across the galaxy began in earnest and captured the imagination of people everywhere. Thousands of would-be-explorers raced to purchase survey vessels and scan the dark expanses of known space with the hope that they would be next to discover a jump point. While many would help discover new resource caches or scientifically interesting astronomical phenomena, only a small percentage would ever successfully lead Humanity to new stars.

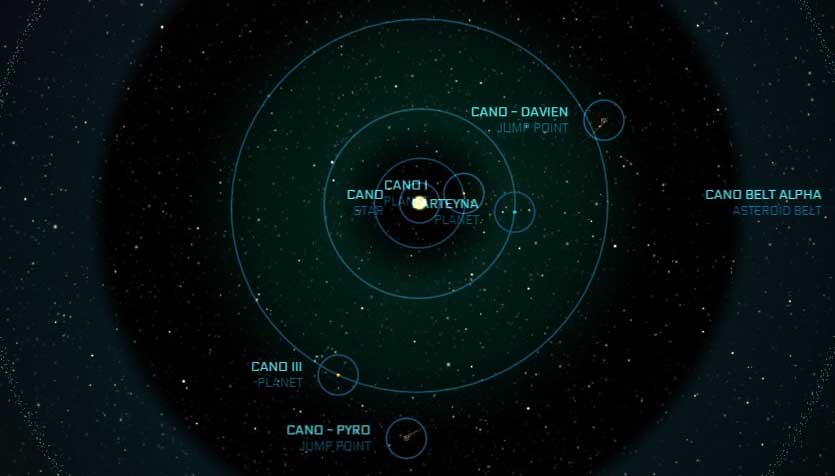

Of these lucky few, Tabatha Caster’s discovery of a jump point was unique in that she made it from the comfort of her home on Mars. Passionate about exploration but unable to travel herself due to a chronic illness, Tabatha would purchase raw scanner data from ships returning from frontier systems like Virgil, Davien and Bremen. Using information collected at known jumps as her comparison baseline, she spent almost all her free time poring through the vast data stores she acquired. Her herculean, decades-long effort paid off in 2463 when she noticed that three different ships had picked up a similar error near the same sector of Davien. While individually it was not enough to trigger any of the standard analysis software of the time, the combined data hinted that there could be something more. Tabatha contracted with Jamel Normond, an independent navjumper from whom she had previously purchased data, to investigate the coordinates. What he found was a previously uncharted tunnel to a yellowish-white G-type main sequence star anchoring a four-planet system.

Initial survey results of “Cano,” a portmanteau of the two discovers’ surnames, indicated that all four worlds were quite inhospitable, a disappointment for those who were hoping for a new world for Project Far Star to settle. Many historians point to this disappointment for helping push forward the decision to attempt the unlikely terraformation of Cano II.

BEST LAID PLANS

An ocean world with a caustic and unbreathable atmosphere, Cano II was far from an ideal candidate. Altering such a dense and toxic atmosphere on a planet with such massive oceans was going to be a significant challenge, doubly so with the technology available at the time. If the proposal had been put forth during a different era, it is theorized that approval for the terraforming project would never have been approved. But with expansion fervor at an all-time high, the voices of doubt were outmatched and the green light was given.

The effort that followed initially seemed like it might actually succeed. Many settlers began to emigrate to the world, setting up the first colony outposts on the permanent glacial ice caps at the north pole. The coastal trading hub of Carteyna rapidly grew to become the largest of these new settlements and reached such predominance in those first few years that the planet itself came to be known by the same name.

Sadly, this early success was short-lived. Atmospheric conditions soon began to deteriorate back to a toxic state and inhabitants were forced to remain inside sealed outposts under the ocean’s surface. However, that first attempt was not the last. With the infrastructure in place and atmospheric self-sustainment seemingly within reach, it proved tempting enough for geoengineers to try again. Plus, there was the financial incentive. If the world could be made more ecologically friendly, its resources would be worth a considerable sum. Over the next few centuries, several more attempts to terraform Carteyna came and went as new geo-technological improvements were tested out, to no avail. This pattern continued until the start of the 30th century, when all hopes of terraforming the planet were dashed for good.

FROM THE DEEP

In 2898, a deep-sea researcher, Dr. Satomi Bechtel, noticed an intricate grooved pattern etched into the surface of a returned underwater probe. Investigating further, she discovered that a colony of microscopic zooplankton known as Canolisca were the ones breaking down the material of the probe. Dr. Bechtel was surprised because the species, studied by previous researchers, had never been known to exhibit this behavior.

For the next few years, Dr. Bechtel dedicated herself to studying the Canolisca. She learned that the distinct pattern was not an isolated case, after finding dozens of sites bearing the complicated markings. The real breakthrough came with the discovery that at regular intervals the markings would become covered with a particular algae in much higher density than found elsewhere in the area. In her groundbreaking 2902 research paper, she proposed that these grooves were actually proof of advanced farming techniques. It was her belief that the last terraformation attempt had prompted an algae bloom that had provided enough resources for the Canolisca to begin developing societal specialization and that the zooplankton colonies were becoming advanced enough that they could be considered on the verge of sapience.

A FAIR CHANCE

As the paper drew widespread attention, scientists and xeno-rights advocates were quick to call for the protection of this developing species under the Fair Chance Act. However, the situation was unique in that previously the FCA had only been enacted on newly discovered worlds. So far there had yet been a situation where a species was classified for protection hundreds of years after Human settlement. FCA status was granted with the understanding that the inhabitants would be resettled elsewhere, but the people of Carteyna were quick to launch legal action to defend their rights. Though their position was highly unpopular, owing to the Empire’s fascination with the Canos (as they came to be colloquially called), it was far from a clear-cut matter. It took years of legal back and forth before a compromise known as the “Cano Species Development Accord” was reached.

Under the terms of the Accord, the local government established an administrative body known as the Office of the CSDA to protect and manage the oceanic sector where the Canolisca are developing. Off limits to all but approved scientists and personnel, the Office of the CSDA maintain a security force to ensure that the zooplankton are left undisturbed. In addition, all resource collection would be strictly managed, there would be no further terraforming attempts, and those living on the world would be limited to the main arcologies already established at the North Pole. In return for the sacrifices made under the Accord, the families who had called Cano home for generations would be allowed to continue to make a life there. In fact, thanks to the renewed interest in the system from the discovery of Canolisca and the inflow of credits from UEE research grants, there might never have been a better time to live on the Cano system than right now.